Gregorian Chant

Thesaurus pretii inestimabilis…Sacred music is a treasury of inestimable value. The Church esteems liturgical chant as a precious gift, belonging to the living tradition, a body of works that give music the title “greater than that of any other art.”

Beginning Resources

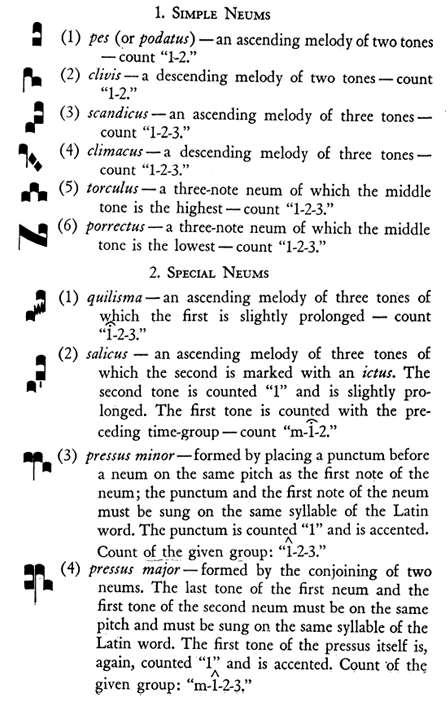

Basic Chant Notation

Chant Interpretation

J.H. Desrocquettes: Gregorian Musical Values (1960)

Dominic Johner: Chants of the Vatican Gradual (1934)

Joseph Gajard: The Rhythm of Plainsong (1943)

André Mocquereau: A Study of Gregorian Rhythm (Le Nombre Musical Grégorien) (1932)

Primary Chant Books

Antiphonale Romanum: Roman Office, Extraordinary Form (1960)

Cantus Selecti: Chants for exposition and benediction, including many seasonal pieces (1957)

Cantus Varii: A collection of chants for Benediction and the Office (469 p.) (1928)

Chants Abregés: Simplified Graduals and Alleluias (1926)

Chants of the Church: An anthology of commonly used chants, in standard square-note notation (1953) | (also available for purchase)

Chants of the Church (in modern five-line notation) (1954)

Communio: Gregorian communion antiphons for Sundays and solemnities; suitable for Ordinary Form or Extraordinary Form Masses

Graduale Parvum: Simple proper chants for Ordinary Form Masses, in Latin and English (2012 ed.)

Graduale Romanum, 1961 edition The standard chant book for Mass, containing propers and ordinary; this 1961 edition is used for EF Masses

Graduale Romanum, 1974 edition The standard chant book for Mass, containing propers and ordinary; this 1974 edition is used for Masses in the modern Roman rite

Graduale Simplex: Simpler chants for Ordinary Form Masses (1975)

Graduale Triplex: A limited-access copy of the semiological reference work from Solesmes (1979)

Graduals, Alleluia Verses, and Tracts: Psalm-tone settings of the propers for EF Masses (1955)

Gregorian Missal, first edition (1990) : Latin proper chants for Sundays and solemnities (according to the modern calendar). Mass ordinary settings. Instructions and text translations in English.

Kyriale (Sandhofe transcription): Transcribed from the Vatican edition Kyriale, without Solesmes rhythmic notation

Kyriale (Solesmes ed.) Chants for the Ordinary of the Mass, excerpted from the 1961 Graduale Romanum | Purchase

Liber Brevior: A handy book for Sunday Masses (EF); similar to Liber Usualis but without Office chants (1954)

Liber Usualis: Chants for Mass and Office for Sundays and most feasts; includes scripture readings in Latin; this 1961 edition is suited for EF Masses

Mass and Vespers: Chants for Mass and Vespers, with scripture readings. Instructions in English (1957)

Offertoriale with Offertory Verses: Gregorian offertory chants, in longer form with additional verses (1935) | Purchase

Ordo Hebdomadae Sanctae juxta ritum monasticum: EF Holy Week and Easter Octave Offices and Masses, including the Passion readings, according to Benedictine usage (1961)

Parish Book of Chant (2nd ed.): A collection of basic chants for Mass (Mass ordinary settings), Benediction, and seasons of the church year

Le Petit Office de la Très Sainte Vierge : The Little Office of the BVM, noted in plain chant (Solesmes, 1893)

Proprium de Tempore (1961): Propers for Mass for the church year; excerpted from the Graduale Romanum 1961 (EF)

Simple Offertory Verses (Richard Rice): Psalm-tone settings of the offertory antiphons: arranged for the EF calendar, but also useful for OF

Simplified Graduale, Major Propers (R. Rice): Well-adapted chants for use in EF Masses; preserve elements of the authentic Gregorian melodies while also using psalm-tone formulas for parts of the text

Versus Psalmorum et Canticorum: Psalm verses, pointed for use with EF Introits and Communion Antiphons

Supplemental Chant Books

Graduale Romano-Seraphicum (1924)

Graduale Romanum (Pustet, 1871)

Introduction to the 1974 Graduale / Ordo Cantus Missae (in English)

Officium Majoris Hebdomadæ et Octavæ Paschæ (Sung Liturgy of Holy Week) (1923)

Ordo Processionum (Franciscan 1925)

Parish Book of Chant (PDF, 1st ed.)

Processionarium (Dominican 1913)

Proper of the Mass (psalm-tone settings) by Fr. Carlo Rossini (1933)

Propers of the Mass for Sundays and Holy Days (Guam, 1962 Missal)

Engraving & Online Media

Regional Chant Supplements

Playlist - Introit & Communio

Gregorian Chant, Words of Wisdom

Song is natural to man, and is already discernible in ordinary speech. Man, in speaking, naturally raises and lowers his voice, thus producing a kind of music: the accentuation of language. ‘Accentus’ = ‘Ad cantus’, that is, a series of inflections of the voice which, without being precisely a song, is something approaching it. ‘Accent is the soul of language’, ‘Accentus anima vocis’. When, in speech, thought takes wings and feelings are heightened, accentuation is intensified as well, bringing itself into musical accord with what the soul is experiencing. It assumes a richer and more powerful form: it turns into song.

The music can divest itself of the word. It can seek the effects of art, since there are innumerable metrical or melodic ways of combining the notes, which are distinct, now, from the words. In general, such effects are more inclined to flatter the senses than to assist the soul. Sacred music, which speaks to the soul to unite it to God, particularly Gregorian change, which is sacred music par excellence, makes little use of these effects of art, or at least rejects whatever is too human in them.

It is always the words that inspire the chant. And the chant, which is the height of accentuation, breathes life into the words, imparting to the rhythm its characteristic ease and freedom, which is comparable to the rhythm of speech. For the rhythm always flows from the words as from its original and natural source.

-The Right Reverend Dom Joseph Pothier

The School of Gregorian Chant at Solesmes.

At Solesmes, this is how we set about establishing a musical text for a given piece of chant from the Gregorian repertoire. I say ‘we’ advisedly, because not only does it put me at my ease by freeing me from speaking as though I were the sole authority, but it also expresses a reality which it is good to publicize. It is, in fact, a whole school, a whole workshop which is on show, and I who am addressing you atthis moment in the name of the ten or fifteen members of this school, this workshop, am no more than one of the team, subject myself to their scrutiny, just as they are to each other’s and to mine.

Neither here, nor in what follows is there any unnecessary display of scholarly apparatus — merely the enunciation of a preliminary guarantee, the guarantee which is given by work that has been checked in this way.

Dom Guéranger himself laid out the foundations of our school. In his Institutions liturgiques, this is how he, who was first in the field, formulated the principle of restoration:

When manuscripts of differing periods and countries agree upon a particular reading, we can safely assert that we have discovered the Gregorian phrase.

That was an indication that we would need to have to hand the greatest possible number of manuscript Graduals and Antiphoners, of all periods and from all parts of the world, ready for the day when we would seriously wish to rediscover the Gregorian tradition in the only sources containing it.The Solesmes work of restoration, planned long before by Dom Guéranger, did, in fact, start there. At first we had to make do with hand-written copies; later, we profited greatly from the new facilities offered by photography.

It was, indeed, mainly in order to further that work, and also to bring about a closer association between lovers of the chant and the study of the sources, that I conceived the idea of founding Paléographie musicale. Ten or twelve years ago, this work of manuscript reproduction suddenly increased and grew by leaps and bounds. But it has been chiefly over the last few years that the Solesmes library hs grown out of all proportions, enriched with copies and photographs representing, either in whole or in their principal parts, the documents recognized as being necessary to the work we had undertaken. The number of photostats runs already into thousands.

Here, then, is a second guarantee: not only do we have the personnel and the system of mutual checking: we also have at hand the materials we need — not, to be sure, in such abundance as we ourselves would have wished; but certainly of such variety, from so many different regions, of such value, and all of them under one roof, so that without a doubt, nowhere else at the present time could anything like it be found. I cannot tell you the amount of research and the number of sacrifices of all kinds that the assembling of such a collection has entailed.

–Dom André Mocquereau

The Theology of Sacred Music

The Theology of Sacred Music

“[The musical tradition of the universal Church is]—in what the council called “thesaurus praetii inestimabilis”—the treasure trove of inestimable value which belongs to the Church Universal and Her musical Tradition. The Church in these words of the last Ecumenical Council has placed before us Gregorian Chant as the most perfect musical expression of Her Divine worship, Her Sacred Liturgy. That being the case, obedience alone, on our part, would be an adequate response.

But as St. Augustine points out, in his 26th tract on St. John’s Gospel, “it is little enough to be drawn by the will, thou art drawn also by pleasure”. Or is it the case that whilest the senses of the body have their pleasures, the mind is left without pleasures of its own?” Augustine then concludes that we need to be what he says “drawn by the bonds of the heart”.

What we today call “Gregorian chant” is the music in which Holy Mother Church has embodied her message from the earliest days of the Christian era. The music she has safeguarded through the centuries as her official form of musical expression. The music through whose strains, even today linked to the Heiroi Logoi, the Holy Words of the Sacred Liturgy, through those words the Church today still teaches, the Church meditates, the Church prays, the Church mourns, the Church jubilates. The insights which have developed during the decades of the recent past are leading us to a fuller appreciation of those methods which the Church has consistently used in the transmission of her message.

Psychology is revealing the fact today that a conscious content strictly confined to the intellect lacks vitality, lacks power of achievement. Every impression, tends by its very nature to flow out in expression, and the intellectual content, content that is isolated from “affective” consciousness, will be found lacking in dynamic, genetic context because it has failed to become structural in the mind and remains external therefore. From this evidence in this field we may safely formulate as a fundamental principle of formation, that the presence in consciousness of appropriate “feeling” is indispensable to mental assimilation.

Now if appropriate “feeling” is necessary to assimilation, it must be equally needful for the assimilation of Religious truth, just as much so as it is for other branches of knowledge. And so we can understand the importance that the Church has always attached to an appropriate musical expression of Her Dogma.

We understand the Church’s insistence upon music of a specific kind which will not merely stimulate the feelings in a general way, but which will embody Her Dogma and Her prayer in an appropriate form of expression.

According to St. Pius X, the function of Musica Sacra is summed up, he said in the two words: vivificare and fecundare. Vivificare means “to add life to, to vivify.” Fecundare means to add efficacy, to render effect on. There are two ways in which we can expect music to add life vivificare and efficacy, fecundare, to the Sacred text. One way is by an enrichment of the Doctrinal content through symbolic use of themes. Think of the example I gave, “O Sacred Head Now Wounded”. What that suggests, just hearing the beginning of the tune.

The other way in which we can expect music to add life and efficacy to the text is by supplying that power, that energizing force, which feeling adds to a merely abstract intellectual concept. The Church through all forms of her organic teaching, aims at cultivating feeling, but she does not allow her teaching and formative activity to culminate in feeling, which she values chiefly as a means to an end. The Church employs feeling in order to move into action, and to form character, and she never leaves that feeling without the stamp and the guidance of the intellect. Dogmatic time. As the feelings glow to incandescense, she embarks to their definite direction, and animates them with a purpose, which after the emotions and the feelings subside, remains the guiding principle of conduct.

To those two formative functions of appropriate sounds, music added to Sacred words, we might add a third function, namely to cultivate an ability to distinguish between different types of emotional appeal, and then to respond only to the highest.

All of these, my friends, are essential elements to be considered in the formative function of Musica Sacra and particularly of Cantus Gregorianus, that integral part of the solemn sung Liturgy. In all three of these respects, that chant of the Church stands supreme. Chant enriches the doctrinal content by lifting into consciousness in a new significance, certain associated ideas, by means of a series of “sound pictures” taken from offices which are mystically related to each other. A wonderful example of that sort of enrichment is the Mass for the Dead, the Gregorian Requiem Mass. Some of you remember it. There the music is a “living tissue of related sound pictures” which add to the content of the print, or the spoken word, and bring a message of consolation and of hope to the ear which is attuned to perceive it. As we sing “Requiem aeternam” and ask that the soul of the deceased person may be forgiven his sins,

and helped by Divine Grace to reach eternal joy, that melody lifts into consciousness the scenes which ushered in the dawn of our Lord’s Resurrection: the chosen vine, the branches, the power of the Word of God, the hart panting for the fountains of water, Sicut cervus desiderat ad fontes aquarum of Easter Vigil, and finally the shout of triumph of Holy Saturday, Laudate Dominum omnes gentes. All that resonates along with those sounds. But should the mind fail to catch these symbolic applications, it can hardly fail to realize the mystical intent. Whereby the melody of the Gradual, Requiem Aeternam, is almost an exact replica of the triumphant Gradual of Easter Sunday. Here our appeal that the soul may reach eternal life, is expressed with the same sounds, the same musical formulae, which at Easter announced the day which the Lord had made for exaltation and joy. And by chanting those words that way we assure ourselves that the soul of the just is held in eternal remembrance, cannot be touched by the powers of evil. The same strains which at Easter expressed our confidence in God’s goodness and his everlasting mercy.

This close linking together in melodic identity of death with Resurrection, and with that one supreme victory over death which is the hope of the individual soul, is more realistic, more convincing, in music than it could be in any mere verbal connection. As a matter of fact the words attempt no such exact parallel. The implication is there but the music that goes with the words in the missal makes that link explicit. Indeed the music goes one step further in its suggested power and reminds us of the guardian angel whose loving care is untouched by death. It weaves in a mystical reference to the eternal marriage feast of the lamb, to raise the hearts of those who know the gradual of the wedding Mass, the votive Mass pro sponso et sponsa. Thus does the music enrich the doctrinal content by what we might call a symbolic code of musical cross-reference.

Through her music secondly, the Church supplies us with a key to the different degrees and qualities of feeling which distinguish one season from another, one feast from another, during the course of the Liturgical Year. It teaches us not only when, but how the Church mourns, for example. Not only when but how the Church jubilates! And much of this is conveyed by the music alone. For example, the single word “Alleluia” recurs over and over and over again in the Church year. In the printed or spoken word, there is no change from season to season. The music alone supplies the commentary on that text, and conveys the difference of quality between the joy of one season and another, between one feast and another. Here indeed we might say we can find “the rainbow shades of the praying Church’s moods” translated into music and clothed with infinite variety. From the tentative and humble tones of the Alleluia of Holy Saturday, when the soul can hardly believe in its own salvation, when the price of the

sacrifice is yet too close at hand to forget the pain which won our triumph, through the gradual crescendo of joy and exaltation to the feast of the Ascension, through the mystical renewal of Pentecost, and the innocent in fact almost naïve rejoices of Christmas: all of those shades of feeling are contained in the music, which gives its true character to the unchanging word, vivifying the letter, the letter which killeth, by adding Spirit which giveth life.

It is plain, my friends, that all of this is formative of Catholic feeling, educating in the highest sense. Because if music in general can influence feeling—ask any music therapist about that—then this particular music is, and must remain par excellence the formation and education of genuine Catholic feeling. If it is the function of Catholic catechesis, of new evangelization, as we say today, to form the minds and consciences of young and old Catholics through sound doctrine, it must be no less its function to form their hearts through sound feeling, that there may be no contradiction between truth and its expression. Failing this, the heart seeking beauty may per chance find satisfaction elsewhere; and dogma become inarticulate, may sicken and die.

This, my friends, explains the psychological basis for the Church’s insistence on a particular form of music. The Church did not leave to chance this formation of the emotions, but taking the arts to herself, she shaped them to her own purpose. The Church in her teaching reaches the whole human person: intellect and will, emotions and senses, imagination and aesthetic sensibilities, memory and muscles, powers of expression. She neglects nothing in man, she lifts up his whole being, strengthens and cultivates all of his faculties, in their interdependence. And that explains the words of St. Pius the Tenth, when he set before us Gregorian chant as the type or norm, the “Supremo modelo” of Christian musical prayer. And its function as he put it, “to raise and form the hearts of the faithful in all sanctity”.

In other words, my friends, there is also classical standard or type of Christian expression, just as there is a classical standard or type of Christian life. As the Saints and the Martyrs are placed before us as models for our imitative faculties in the realm of Christian living and action, so too in Gregorian chant, we are given models for our imitative faculties in the realm of Christian feeling by which to orient our emotion, from which and with which our actions arise.

Rev. Msgr. Robert A. Skeris, D. Th.

Having served as Professor and Prefetto della Casa at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, Consultor to the Vatican’s Office of Pontifical Ceremonies, Msgr. Skeris has been on the faculty of the University of Dallas, Christendom College, Director of the Ward Method Studies at Catholic University of America, and was a co=founder of the Church Music Association of America.